DAROS LATINAMERICA: MEMORIES BEHIND A DANGEROUS LEGACY

The history of the great events of this world

are nothing more than the story of a crime

Voltaire

INTRODUCTION

This text comes from a special situation. During the investigation I advanced to the article on the Art Museum of the National University in Bogota, I was struck by this close relationship between the cycles exhibition of this museum and its director/curator with Daros Latinamerica collection.

The obvious question was beginning to resolve who was Daros? It immediately came to my mind to assume that it was a Swiss company and this was enough to confirm exploring the web site collection. Keep in mind that there are three Daros collections: the Classic to call it, the one which is dedicated to Latin American art and the other one who collects European contemporary young artists, in the words of Stephan Ernest Schmidheiny.[1]

On page of the Daros Collection you read that Alexander Schmidheiny (brother of the first) started this company with his partner Thomas Ammann in the 80s, focusing on the art of the second half of the twentieth century, especially American art with its emblematic figures as Andy Warhol, Cy Twombly, etc.

The premature death of Alexander and Thomas Ammann took to Stephan Schmidheiny to continue the collection. But his interest in this collection was coming before, as assistant financial interests of his younger brother in art from the beginning, according to a statement that I would transcribe, taken from his autobiography:

Nevertheless, my business activities in the 1980s reflected uncertainty and concern. Art proved to be an excellent antidote to stress. This was the time when my younger brother Alexander and his partner introduced me to the world or modern and contemporary art. With my financial assistance, the two of then started a high-quality contemporary art collection; at the same time, my interest in the works they acquired began to go beyond that of a mere investor.

By that time, the question was not who Daros was, but who was Stephan Ernest Schmidheiny? And then I received a direct jap to the certainties that help understand where fiction begins and where reality ends, because their blends reach drawing in the space of experience a landscape completely absurd when its diffuse boundaries lines disappear, causing these same certainties lose confidence in that place between magic and dark where art fictions circulates.

When you place in Google the name of this gentleman, the information is contradictory. It’s like the prelude to the remastered universe of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

On the one hand the Schmidheiny’s website handles describing a man of good manners that makes philanthropy in Latin America. Moreover, the information shakes the reader with tons of documents that speak of the trial of Turin and the condemnation that has dealt the good of Schmidheiny, as owner and last heir to a dynasty that was involved in the business of Eternit, I mean asbestos, for much of the twentieth century.

From that moment, my interest turned to unravel this huge ball of asbestos-related information and all (as far as possible) the lies and truths hidden behind this powerful industry that moved billions of dollars over the twentieth century and continues to do so in emerging countries, of which Colombia is no exception.[2]

Understand the procedures in this industry for a century is also to understand a bit the mind of a collector, and any purposes that led to seed a whole strategy around Latin American art of the last decades, although Hans – Michel Herzog intends to put Stephan Ernest Schmidheiny out of any link with this collection ¿Is art a refined model that contemporary life auction to access and buy indulgences?

Understand where the money comes from to pays this festival of art and from where goes out the checks that feed the dreams of artists, is to find a perspective to understand the logic of some European modernity built on the foundations of progress, freedom and civilization. This progress at the time was called asbestos and could be called a thousand of inventions, other news, other freedoms, be they scientific, economic, social or cultural.

When I think that the discourse of the historical avant garde followed the logic of capital movements, sometimes product of strategies that counter-acted but were captured and realigned again by the capital, thanks to the economic power of collecting, I cannot ignore – according to McCulloch & Tweedale – the Industry’s peak in North America and Western Europe coincided with what some economists called the “Golden Age of Capital” (1945 – 1972) and in that sense asbestos is symbolic of modern industrial production and its attendant global divisions of labour[3] and thus, a precursor of capitalism without borders, which serves as a platform for establishing specific models that ended following not only global trade but several discourses and forms of circulation for contemporary art covered in globalization post nations.

In a curious way or coincidental, I was working on the translation of the text that Andrea Fraser had sent to the Whitney Biennial this year 2012 and entitled “There’s no place like home”.

Early Andrea tells she is without visiting exhibitions for quite a few years and museums and to justify this position says:

I can rationalize this remove as stemming from my alienation from the art world and its hypocrisies, which I have made a career out of attempting to expose. I have ascribed to institutional critique the role of judging the institution of art against the critical claims of its legitimizing discourses, its self-representation as a site of contestation and its narratives of radicalism and revolution. The glaring, persistent, and seemingly ever-growing disjunction between those legitimizing discourses— above all in their critical and political claims—and the social conditions of art generally, as well as of my own work specifically, has appeared to me as profoundly and painfully contradictory, even as fraudulent.

At the end of the text, in the notes appeared a reference to another article that Fraser had published in the German magazine Text zur Kunst in September 2011 entitled “L’1% C’est Moi”, where she established that relationship between big money and art collectors. Much analyzed collectors had their share of responsibility for financial and mortgage crisis of 2007, which allowed Andrea Fraser to perceptively stating:

¿How do the world’s leading collectors earn their money? How do their philanthropic activities relate to their economic operations? And what does collecting art mean to them and how does it affect the art world? If we look at the incomes of this class, it is conspicuous that their profits are based on the growth of income inequality all over the world. This redistribution of capital in turn has a direct influence on the art market: the greater the discrepancy between the rich and the poor, the higher prices in this market rise. Except to stalwart adherents of trickle-down theory, it must be abundantly clear by now that what has been good for the art world has been disastrous for the rest of the world.

I immediately realized the relevance of these words with the regional theme of Daros Latinamerica Collection, its owner behind racks and likely targets of such an organization intends to seek at investing so much money in this seemingly noble cause of art in the region.

With the collapse of the asbestos industry in European countries, good Mr. Schmidheiny searched to start to shift his investments to this region of the Americas. It was famous the family sharing in Eternit plants throughout Latin America, such as in business Managua reconstruction after the earthquake in 1976, when allied with General Somoza created an Eternit facility in Nicaragua.

Similarly, during the dictatorship of Pinochet, a law ignored all previous treaties between the Mapuche and winkas (white people), imposing the division of land among members of indigenous communities, ending with collective ownership, so family camps were set too small to be profitable[4], which paved the way for investors and landlords as Schmidheiny were made to several thousand square kilometers of virgin forest purchased at very low prices to the Mapuche Indians, who at the time of the dictatorship were forced to sell. “Mapuches no longer exist, because we are all Chileans,” said Pinochet in 1979.

Today these lands produce much of the wood we use in Latin America under the name of Masisa, which belongs to Forest Millalemu controlled by a holding company called Terranova, with forestry assets in Chile on 120,000 hectares distributed between the VIII and IX Regions and forestry investments well in USA, Brazil and Venezuela totaling 295.000 hectares of forest land in addition to industrial operations in Mexico and the U.S., making it the largest producer of pellets in Latin America, with a capacity of annual production of 2.3 million square meters in wood panels, moldings and doors.[5] Obviously the virgin forest has disappeared,[6] and with it the flora and fauna in general because these plantations are not forests and crops but not only crops, but they are fast growing tree monocultures, implemented on a large scale.[7] The biggest mistake is precisely that: Rate of forests to monoculture plantations and even worse, Millalemu Forest has made with Genfor SA pines transgenic experiments in Chile, without any control.[8]

When I thought about the artists who are part of this collection, and especially those who manage socio-political content in his work, I understand fully what Andrea says with a good dose of grafitiada wry smile on my face – between diffuse and hyperreal: what is good for art has been disastrous for the rest of humanity.

Speculations that one can do in this area are spacious and can hardly be evacuated in a single article.

I will divide this research into various chapters and the first will be devoted to unraveling the history of asbestos, of Eternit Switzerland run by this family and their partners in the SAIAC cartel, and of course, the relationship with this poisonous material: asbestos.

The second chapter to be published in February, when Esfera Pública resume their work, will analyze discourse relations and conceptual artists who are part of this collection (Luis Camnitzer, Alfredo Jaar, Doris Salcedo, Miguel Angel Rojas and Jose Alejandro Restrepo) and situations that can be inferred when we look at his speeches and articles in the light of the stories that lie behind the money that fuels this theater of fictions called Daros Latinamerica ¿Why dare I to say this? While artists defend a few things on one side, the company buying their works and promoting these artists, does exactly the opposite on the other.

In this long series of events and situations that make up this chain related to sensitive markets of art and contemporary aesthetics, there seems to be something that definitely does not work, because while the field of production raised some sensitive issues for society overall, the final path of the works and their conversion into luxury goods for the art market seems to completely blur the initial contents of the works of art, and even more, reduce the role of the artist to a cynical player in this market who prefers to ignore these things happening around it, continuing feeding their harangues aesthetic without need or have to take any ethical responsibility for it.

All revolutionary principle of the work of art, as a device not controlled by the status quo, ends in the most simple and banal domestication by the big business or manipulated by the “manufacturing of dissent” to use the words of Michel Chossudovsky,[9] especially when this capital has been forged by deception and crime if you stick to the conclusions that leaves the judgment of Turin.

Not to forget here other part of the Daros Foundation: the subsidy offered to institutions as “Lugar a dudas” directed by Oscar Muñoz and most likely support for “FLORA”, the project led by José Roca.

As expected, no one will say anything. When I published the article on the National Museum of the University not a single statement were made, even of those affected by the vertical policies Maria Belen Sáez de Ibarra does ¿anyone dare to bite the hand that feeds him? The common logic says no, so the hand is a hand genocidal, such as asbestos industry throughout the twentieth century in Europe, Canada, USA, Japan, Africa or Latin America.

PART I

DIRTY MONEY FROM ETERNIT FUNDS THE GOOD CONSCIENCE OF ART: DAROS LATINAMERICA COLLECTION

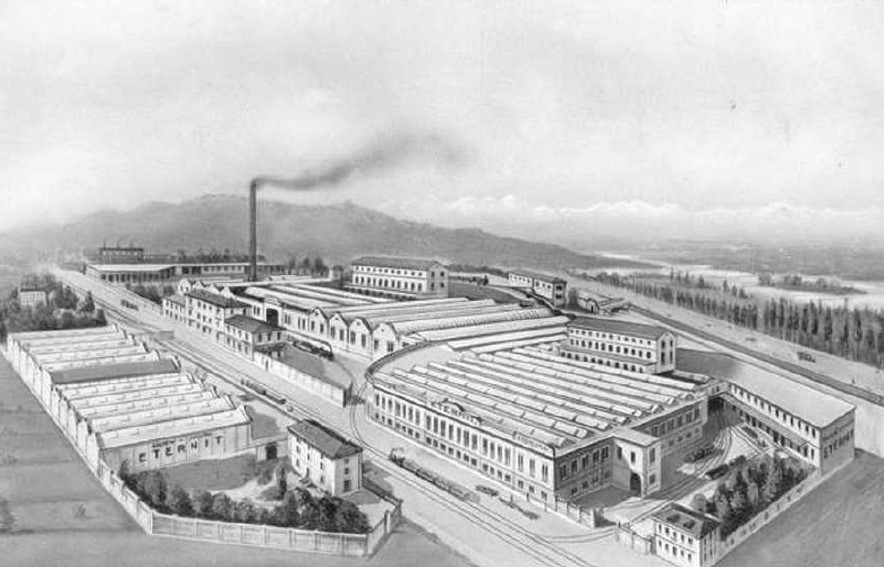

Eternit has been the name of dozens of manufacturing companies and scores of building products; a dominant multinational industrial group, two global asbestos conglomerates, a brand, a patent and a generic term; in many markets, the word “Eternit” is used to denote a range of asbestos-cement building products regardless of the trade mark. But Eternit is more, much more than this described in the next sentences; over the last hundred years, these seven letters have come to represent a production process which uses up and spits out human beings as part of the manufacturing cycle.[10]

Stylized image of the Casale Monferatto Eternit plant in the 1 920s. AFeVA archive

Stephan Ernest Schmidheiny was born in Heerbrugg in eastern Switzerland, located in the canton of St Gallen, on October 29 of 1947, in the heart of one of the most prosperous families, traditionally linked to the thriving business world in always prosperous Switzerland.

According to Forbes magazine, is ranked 442 in the list of wealthy and because of it, the fifth richest man in Switzerland with 2.7 billion.[11]

The Eternit brand was associated with this last name throughout the twentieth century and in this century, seems to be turning into a nightmare that comes to regaining its dose of justice against the huge trail of deaths that asbestos has left in thousands of employees who worked in Schmidheiny’s family factories that were sown throughout the planet.

In ancient time asbestos were used for “magical” and “ritual” purposes. A popular belief said that asbestos would get to be the “salamander’s wool”, the animal that could challenge the fire unharmed.[12]

“Asbestos” is a generic name given to a group of fibrous minerals. Put simply, is a rock that is dug from the ground. Two types exist: serpentine and amphibole. Chrysotile (or white asbestos) is the only member of the serpentine group and is mined mainly in Russia, Canada, China, Brazil, and Zimbabwe. The amphibole grouping includes, inter alia, two important commercial grades – amosite (brown) and crocidolito (blue) – which in the twentieth century were mainly mined in South Africa. Other family asbestos from amphibole group are anthophyllite, tremolite and actinolite. All types of asbestos split longitudinally into fibres. It was this propensity to fiberize that (combined with its heat resistance and toughness) made asbestos so useful. These asbestos fibres can continue to break down almost to molecular level.[13]

When rubbing asbestos between the fingers can make it “smoke” and produce a small dust cloud of fibres of unimaginable fineness. Most can only be seen under an electronic microscope. Such fibres are easily inhaled: even in the thickest clouds, the dust is breathed in with impunity, without irritating the airways – at least in the short term. Over the long term, the impact of inhalation is damaging and insidious. All types of asbestos are capable of producing three incurable and potentially fatal asbestos – related diseases (ARD’s): asbestosis (lung scarring), lung cancer (originating in the lining of the airways of the lungs), and mesothelioma (a cancer of the lining of the chest or of the abdomen). Asbestos may also cause other cancers, such as gastrointestinal tumours.[14]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Ludwig Hatschek invented a process for combining asbestos fibres with cement to produce asbestos-cement (AC), a material which had excellent technical properties and could be used for a wide range of applications. As asbestos would “last forever”, Hatschek named the process Eternit, for eternal, and proceeded to sell the patent to companies all over the world, many of which took the name Eternit.[15] Ludwig Hatschek franchised his invention as “Eternit” and over the next sixty years, licenses were granted to companies in Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, France, the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, Argentina, Hong Kong, Uruguay, China, Nigeria, and India.[16]

Asbestos is present in cement sheeting which clad many homes and water tanks, in the pipes which supplied water; asbestos fibre are blended into vinyl floor tiles and in insulation designed to make oil refineries, hospital, warships, cinemas and domestic dwellings safe. It was used in USA and European countries and keeps being used in developing countries in rubber and plastics products, mixed with adhesives, cements, paints and sealants. In automobiles asbestos is blended into gaskets, cylinder heads, spark plug washers, exhaust pipe insulation, radiators blankets, and brake linings. Some of its more exotic uses include cigarette filters, dish towels, surgical thread, banknotes, piano felts, ironing boards, berets, aprons, carpets, tampons and filters for rice, salt, beer, and fruit juice.[17]

As restrictions were imposed on asbestos in developed countries, new markets were cultivated in developing economies; in recent years, sale of asbestos-cement products in India, Pakistan, Indonesia and Thailand have risen significantly. Despite the knowledge that exposure to asbestos can cause debilitating and fatal diseases, asbestos producers continue to advance the case for the safe use of asbestos, and deny the existence of safer alternatives.[18]

According to Fiona Murie, Director of Health and Safety at the International Federation of Building and Woodworkers (IFBWW) at that time, the notion of the “controlled use” of asbestos is a “sick joke”.[19]

By the time asbestos cement was invented there were already reports that asbestos fibres could cause pulmonary diseases. In 1918 the US Bureau of Labor Statistics went so far as to publish a book which noted that a number of major American and Canadian life assurance firms were refusing to sell any further policies to asbestos workers, whom statistics had shown to suffer a high rate of premature death.[20]

The first mention of claims for damages against an asbestos firm on the grounds of pulmonary disease dates from 1929. The company in question was Johns-Manville. Such claims for damages were also a concern for insurers providing policies against industrial risk.[21]

Scientific interest in the problem increased following the publication in 1924 of a paper on asbestos fibrosis of the lungs in the British Medical Journal. From 1927 a number of further papers appeared in England and the term asbestosis was used for the first time.[22]

It was noted that due to the lack of microscopic and anatomical research in earlier years pulmonary diseases had too frequently been diagnosed as tuberculosis. Confusion also existed over the influence of silicon, silicosis being already recognized as an occupational disease. In the ‘30s and ‘40s more papers were published on asbestosis, dealing with both the disease itself and the number of victims.[23]

No one knows how many lives have been lost due to the widespread and uncontrolled use of asbestos around the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that currently about 125 million people in the world are exposed to asbestos at the workplace. According to WHO more than 107,000 people die each year from asbestos-related lung cancer, mesothelioma and asbestosis resulting from occupational exposures. One in every three deaths from occupational cancer is estimated to be caused by asbestos.[24] Professor Joe LaDou, from the University of California, is even more pessimistic saying:

“The asbestos cancer epidemic may take as many as 10 million lives before asbestos is banned worldwide and exposure is brought to an end… The battle against asbestos is in danger of being lost where the human cost may be the greatest, in developing countries desperate for industry”.[25]

The history of the Schmidheiny imperium began in Heerbrugg, a small village in the Rhine Valley, in the eastern part of Switzerland. Jacob Schmidheiny (1838- 1905), the grandfather of Max Schmidheiny, was the son of a tailor and was originally a silk weaver.[26] After his attempt as a textile manufacturer, he established a series of tile works, starting in 1870. Before that, he had bought the Castle Heerbrugg with a loan from a virtual stranger; the castle remained in the family until the early twenty-first century. In 1906, Ernst Schmidheiny (1871 – 1935), Jacob’s elder son, began producing cement. This would eventually lead to the creation of the Schmidheiny’s vast global conglomerate, Holderbank; the name being derived from the location of a factory in which Ernst Schmidheiny had acquired an interest before World War I.[27]

The most important use of asbestos has undoubtedly been in the production of asbestos cement using the method patented by its Austrian inventor Ludwig Hatschek in 1900. Asbestos cement generally consists of from 10 to 20% asbestos with almost all the rest being cement, in addition to raw asbestos, a ready supply of cement is required in its production. In this regard, it is significant to note that the Swiss entrepreneur Ernst Schmidheiny had as early as 1910 established a cement cartel in Switzerland, and that in 1930 he succeeded, by means of the financial holding company Holderbank Financière, in bringing major cement interests in every corner of the globe under his control.[28] Holderbank thus played an important role in expanding Eternit Switzerland.

In 1929 Ernst Schmidheiny (Uncle of Stephan Ernest Schmidheiny), together with the British asbestos multinational Turner & Newall (T&N), established the cartel Internationale Asbestzement AG, “SAIAC”,[29] which belonged to large international companies related to this industry: Johns – Manville from U.S. and owner of the largest asbestos mines in Canada, and different subsidiaries controlled Eternit in continental Europe, especially families Schmidhieiny in Swiss and Emsens in Belgian, they thought than compete for raw materials and markets was not as profitable if they were not properly organized to control the exploitation, production, distribution and market prices in concert, which ended calling SAIAC (an abbreviation of Sociétés Associés d ‘Industries Amiante-Ciment) which had its headquarters in Switzerland directly.[30]

The cooperation in areas of mutual interest allowed them to fixing prices, designating spheres of influence, coordinating “scientific” research and promoting core propaganda messages in defense of the interests of the industry. The fact that the methods industry used were illegal in some countries and immoral in all did not constrain corporate lobbyists in the pursuit of their ultimate goal: turning deadly fibers into hard cash.[31]

Turner & Newall Ltd., the leading UK asbestos, showed their pride in belonging to this cartel, referring to it in a company’s annual report as a “miniature League of Nations”.[32]

Relatives of asbestos’ victims during today’s hearing of the second trial in Turin (Italy) on Eternit case. Turin (Italy), July 24th 2015. ANSA/ ALESSANDRO DI MARCO

Today, aggressive marketing campaigns, backed by millions of asbestos dollars, are targeting decision-makers and consumers in developing countries. The increase of asbestos consumption in countries which have little information on the long – term consequences of asbestos exposure, no specific asbestos law, no enforcement of the laws which do not exist, no official workplace inspections, no compensations, no health services and no social security, is cause for serious concern. The vulnerability of construction workers in these countries makes exploitation routine; often illiterate; many of them live with their families on buildings sites or by the sides of roads.[33]

On 13 February this year, 2012, Mr. Stephan Ernest Schmidheiny (65 years) and his partner Jean-Louis Baron de Cartier de Marchienne (90 years) were sentenced to 16 years in prison by an Italian court of Turin, the first as owner of the industrial group Belgian-Swiss Eternit (ETEX) which in turn was the majority shareholder of the Italian subsidiary Eternit, and the second one listed as director and minority shareholder of Eternit Italy, for causing “permanent environmental and health catastrophe” and for violating safety rules in their factories. In this judgment they appear as responsible for the death of 3,000 people, former workers or inhabitants of four villages where Eternit Italy had its factories from 1976-1986, a process that is part of a penal social mobilization of almost half a century whose core were and keeps being former workers in the Eternit’s factory of Casale Monferrato as collective actors.[34]

This case represents a long itinerary of the asbestos industry, workers and victims of asbestos use in workplaces, basically by the knowledge that existed by the directives of the asbestos industry that its use was mortal. Precisely Turin trial has undertaken to set an important universal scale precedent of this problem quite unknown in our country Colombia.

The industry, barley for the opportunities offered by working as a cartel, used to hold meetings to track and perfect “state of the art” and thus hone their strategies against the “enemy.”

In a declassified file of T&N conference made by the industry for 24 and 25 November of 1975 in the city of London, it is possible to read and extract the following pearls of a comprehensive summary of strategies that appear in the index of this report: on page 5 the conference of Dr. W. J. Smither was entitled “Use of Asbestos – Some recent advances in the medical background,” page 26 was devoted to “Health and asbestos – Situation past and Present in Holland” by Mr. A. R. Kolff van Oosterwijk (sic), page 30 “Report of the West German delegation” by Mr. G. C. Schmidt, page 45 “Brief review of current and prospective regulations in Italy ” given by Mr. A. Calamandrei, on page 53 the speaker, Mr. W. P. Howard titled his talk “Actions taken in the UK to defend asbestos” and on page 61, in the lecture that gave Mr. W. P. Raines its title was “Brief review of attacks on asbestos and our defenses – USA”.

Mr. M. F. Howe (Deputy Chairman, Asbestos Information Committee) in the words he spoke to welcome this meeting said:

The fact that there are 35 of us here from 11 countries underlines the importance of the subject which we shall discuss. Speaking for the delegates from the Asbestos Information Committee and the Asbestosis Research Council, we are certain that we shall benefit greatly from the exchange of information and ideas. I hope that you, the delegates from the other 10 countries, will benefit similarly.

I know that we are all regarding this as a working conference and it is taking place at a very critical time in the history of asbestos industry. In North America, in Great Britain and in other European countries, severe attacks on asbestos and its uses continues to be made in the press, on television and on radio. In these and many other countries, Government Departments are showing growing interest in Factory and other regulations related to asbestos. Interest in the subject of environmental pollutions is perhaps only now in its infancy. These are the subject which we shall be discussing during our conference.

During World War II, in the heyday of German National Socialism, Eternit Switzerland managed to register his company that was on the outskirts of Berlin (Deutsche Asbest-Zement Aktiengesellschaft, DAZAG), in the register of companies that were important for the Reich to the economy war of the time, and that allowed them to obtain supplies of labor in their factories with prisoners of war that came from countries invaded by German forces to be converted into a kind of modern slaves.[35]

This version continues to be denied by the Schmidheiny family, despite the well documented evidence that appears in the book of Mary Roselli[36] entitled “Die Asbestlüge, einer Geschichte und Gegenwart Industriekatastrophe”, of which there are translations into English (The asbestos Lie, 2007), French (Amiante & Eternit: Fortunes et forfaitures, 2008) and Spanish (La mentira del amianto, Fortunas y delitos, editado por ediciones del Genal en Málaga).

For her research, Maria Rosselli did get to locate Ofsjannikova Nadja with 85 years old at the time of the investigation, resided in Riga (Latvia); she had been forced to work in the Eternit plant in Berlin in 1943. In his account Nadja Ofsjannikova tells:

In 1942, at age 19 I was called by the military command and crowded and suffering cold, we were transported to Germany (…) to an asbestos-cement factory. There we stayed in barracks. The work in this area was higher than our strength. The ship on which we worked had no roof and the cold was terrible. Sometimes I just wanted to die. I cried a lot. The factory where I worked was called Eternit (…) was like a concentration camp, we had numbers and we had to continually teach our tab. (…) We had to work even when sick, twelve hours a day, six days a week. Once I caught pneumonia, but I could not stay in bed (…) food in the camp was terrible: for breakfast gave us flour soup, beet soup at noon and in the afternoon one hundred grams of bread with a little margarine ( …) the caretaker of the cabin watching us all the time and when we not obeyed she grind us to a pulp. Sometimes I wonder how I could endure much suffering (…). In April 1945 we were bombed again, but luckily we were able to take refuge in the basement (…) In 2000, when I learned that people who had been forced to work receive compensation headed for the Archive, but there consisted that I had gone voluntarily to the field. I sent a letter to the Eternit factory, but received no reply.[37]

Although Maria Roselli documents found in German archives show that Ms. Ofsjannikova worked as a clerk slave for Eternit, Stephan Ernest Schmidheiny spokesman – I repeat – continues to deny that this practice occurred.

In 1930, Eternit Switzerland bought a number of small mines in South Africa, creating Everite. The book describes this step of Eternit Switzerland by the South African Apartheid, where large economic benefits obtained by hiring cheap black labor, where besides the shameful wages workers were condemned to a silent occupational death which the company never showed any interest to investigate.

Another section of the book that I took from the web page by Paco Puche, not from the book directly, I would transcribe the following note:

No less impressive is the interview that the author recounts in the book with a South African trade unionist. Goes like this:

– What were the working conditions in factories Everite, owned by the Schmidheiny, asks the author.

– It was completely terrible replicates the interviewer: there was dust everywhere and no one told us it was deadly: When someone got sick they sent him to his “homeland”,[38] but nobody knew what our comrades died.

– Workers had direct contact with the management of the company?

– For years we became the question why the management of the company, especially the directors come from Switzerland, avoided going to work in the ships? It was much later when we realized that they would not wanted to breathe the dust; they knew from the beginning that it was mortal.

– Did the direction of the Swiss company explain why they sold the factory in 1992?

– The reason was clear: with the end of apartheid could no longer exploit blacks to paying much less than whites … We got in those terrible workers houses where we lived for decades without our families (…) This is the reason why Stephan Schmidheiny left his business with South Africa. He set foot in “dusty” before the new government forced him to take responsibility. We write to Switzerland clearly informing that it had to meet their responsibilities and compensation to patients and families of the deceased. No answer, but we received a letter from the leadership of its new holding company, in which they communicated that they acted at all times in accordance with South African laws in force (of apartheid) and therefore have no responsibility in legal or moral terms – The South African law does not allow workers to sue their former employers (Interview with Fred Gonna, South African trade unionist who worked 25 years in a factory of Schmidheiny).

Indeed, since 1942, under the apartheid regime, some 55,000 people worked for different companies for the Schmidheiny, most blacks without rights. Stephan Schmidheiny formed in business management in the South African firm Everite, belonging to the family. During the seventies he commanded all Eternit factories they owned in the world and was one of the largest shareholders of the South African company Everite in the worst years of apartheid, in the time when racist repression apparatus spared no half to stay in power. They owned Mines of crocidolite (blue asbestos), noted for its carcinogenic potential.[39]

Not to mention Somoza’s Nicaragua, during the earthquake that devastated Managua: as black angels of industrial modernity, they came with his inventions of asbestos cement to do business with the regime and rebuild the country offering their tiles, their pipes and their water tanks at very good prices, through a company in which they share society with the dictator called it Nicalit. The biggest beneficiaries would be the poor, spreading the city with asbestos everywhere, like a good portrait of many third world cities who still believe in the economic benefits of using this material.

According to Brazil’s Fernanda Giannasi, Asbestos-cement production in Osasco, in the metropolitan region of São Paulo, began in August 1942. During the military dictatorship and with good relations with the military officers in power and their complete support, the extension of the asbestos-cement business to more distant regions began, decentralizing the business from the Rio de Janeiro–São Paulo axis.[40]

In the last decade of the 20th century (although information on the exact date is contradictory), the Swiss group officially withdrew from the asbestos business and Eternit was sold, falling under the control of the French group Saint-Gobain, its partner in SAMA.[41]

Everything seems to indicate that the Swiss group was secretly involved with the asbestos business in Brazil until at least 2001, according to the testimony of Élio Martins, the current President of Eternit at that time, even though the official propaganda publicly denied any involvement after the early 1990s.[42]

The proof of Eternit’s irresponsible behaviour in Brazil, was the fact that in 1987 the physician in charge of occupational health for Eternit admitted during an official inspection by the GIA (Interinstitutional Group on Asbestos of the Federal Ministry of Labor and Employment) of the Osasco plant, that he knew of six cases of asbestos-related diseases. Furthermore, it became clear that none of these cases were reported to either the relevant Brazilian health or social security agencies, as required by law, due to a decision of Eternit’s headquarters office in Switzerland.

The order, which came directly from Switzerland, was that the cases of workers who showed signs of asbestos diseases would have to be filed individually by their own lawyers with the courts. Such were the policies of “social responsibility” at Eternit in Brazil![43]

This behavior of Eternit in his heyday by its directives is hard contrasted with the new role that Ernest Stephan Schmidheiny ended assuming.

In the early 90s, Schmidheiny began to self-promoting himself as “a business person that highlighted innovative green concepts such as “eco-efficiency” “social responsibility” and “sustainable development”, these concepts were cleverly manipulated at the summit of the earth, developed precisely in Brazil, where many employers have committed to the reorientation and implementation of these policies in their companies. An example is Eternit Brazil, where the company has consistently refused to pay decent compensation to their workers or members of their families because of asbestos exposure in the vast plant in Osasco.

The amount of donations Stephan Schmidheiny has made are 1 billion dollars in Latin America, but while this happens, thousands of people around the world have to cope alone, helped only on the support that their families provide, dealing with a disease that slowly and painfully kills their lungs, without a clear political responsibility for these acts.

Whenever the company or the actual Schmidheiny made payments for these situations, these are given under the form of compensation which requires the beneficiary to waive their rights to demand. This figure was used and is still used in Italy, where Schmidheiny has major legal trouble. During the trial stage sought to use this figure to weaken the coalition of interests who arrive it united to the trial. If these facts are treated together take on a very different legal level if that occurs solved individually. In this issue, the Italian jurisdiction is introducing innovative ways never before contemplated in the labor laws of universal nature.

From the moment that the people of Casale Monferrato began building its legal strategy – always together – Schmidheiny began to move quickly to dismantle the movement.

Among its strategies appeared the idea of hiring a public relations office in Turin (GCI Chiappe Bellodi Associates), to track the process. Each and every one of their players began to be spied on, starting with the prosecutor Guarinello. An undercover reporter paid by the office, reported all press reports and all movements of Casale Monferrato leaders that the case occurred. AFEVA Bruno Pesce says: “She spied on us day after day, year after year, attending all the union meetings, asking questions on the proceedings… Schmidheiny was paying the Bellodi practice which paid its informer(s)…”[44]

For many years evidence that mesothelioma, asbestosis and lung cancer was caused by asbestos was a really big companies associated with the business of asbestos knew, but did everything possible to make that truth would never come to the view much less public and their workers. And in this case lays the great tragedy of asbestos, a mineral that symbolizes progress and ideas of industrial modernity in the twentieth century, hidden behind the infamy and economic benefit on the lives of people.

Also when it comes true, the asbestos industry is a mine to manufacture them. According to Laurie Kazan – Allen, war of asbestos is adequately covered in a declassified document from the Asbestos Institute where you can read: “The subject heading is: “WAR report.” Following the collapse in Western demand for asbestos, producers have mounted a global campaign to protect remaining markets and develop new ones. Access to generous funding from their supporters has enabled pro-chrysotile lobbyists to bombard government officials and journalists in the developing world with offers of “technical assistance” and free trips to Canada; a welloiled propaganda machine reassures civil servants and consumers that asbestos can be used “safely under controlled conditions,” despite a vast amount of scientific and medical evidence which proves otherwise.[45]

Given this avalanche of misinformation and industry experience in these matters, nothing better than having big media friends to continue the lies. Sometime Forbes magazine published an article on Stephan Schmidheiny calling him the Bill Gates of Switzerland, sometime after the Italian Fiscal Rafaelle Guarinello accused him of “intentional and ongoing environmental disaster” and “willful neglect to implement measures regulation to guard the health and safety of their employees.”[46]

After this asbestos magnate put his heels in Europe in terms of investment, decided to dump their good intentions in Latin America, creating a philanthropic foundation called VIVA SERVICE (Viva Service represents the link between – New Group and social activities – Avina foundation and its environmental and social activities.)

Paco Puche of Spain, who has been following Avina explains: However, my approach to this work as editor was not the result of the anger and pain of lost friend, but research on the Swiss magnate Stephan Schmidheiny, one of the world’s richest men, who had taken a few years ago my partner Elizabeth and myself, on the trail of a philanthropic foundation founded by magnate called Avina. The aforementioned foundation devoted huge amounts of money to do business with the poorest of the labor and other social movements, NGOs, under the seal of the corporate social responsibility and what we now call green capitalism. We understood that this foundation was penetrating social movements above and disable this implied in resistance to capitalism, especially in Latin America, using as a bridge to the Spanish leaders. Also I understood that behind this “generosity” was “fishy”.[47]

The Avina Foundation, which likes to boast how it has “financed social and environmental projects in 12 Latin American countries” to the tune of US$280 million, including support for 130 projects in Brazil alone according to Época magazine, however, Avina never donated a penny to associations of Brazilian asbestos victims (ABREA). For proof of this statement, allow me to quote a message ABREA received from Geraldinho Vieira, the representative of the Avina Foundation in Brazil, dated April 16, 2004:

“We received your application for support for the publicity campaign to educate the public regarding the eradication of the use of asbestos and for the creation of a center specialized in the treatment of victims of that referred raw material. I must inform you that such project doesn’t fit into the goals and objectives of the Avina Foundation.”[48]

Those left behind to run the factory were workers like João Francisco Grabenweger. At 77 years of age, 38 of them devoted to Eternit, Grabenweger can barely draw enough breath to walk. In exchange for lungs ruined by asbestos, he earns $1,308 U.S. dollars a month in retirement income. A resident of the state of São Paulo, descendant of an Austrian family, he remembers the young Stephan Schmidheiny, who would chat with him in German. ‘His major sin was failing to shut down the plant so that nobody else would have contact with the asbestos,’ regrets Grabenweger.[49]

On December 19, 2003 the same João Francisco Grabenweger wrote a letter to Schmidheiny in German in which he told his former “workmate” at the Eternit plant in Osasco about his pain and anguish. Following are some of the most gut-wrenching passages from Grabenweger’s letter:[50]

“Do you remember, sir, the time you spent as a trainee in your Osasco factory in Brazil where you worked in the departments, and did the work of both ordinary laborers and foremen? At that time I was assigned by factory management to work together with you throughout the factory, because I was fluent in German. I am Austrian descendent and my name is João Francisco Grabenweger. I don’t know whether you still remember this humble worker with whom you used to talk about your passion for underwater diving, mostly in the Mediterranean Sea. I went with you, personally, to the Butantã Institute, which is world-famous for its collection of live snakes and for its production of anti-venom serum against snakebites and other vaccines.

My life as a worker at Eternit’s Osasco plant began in 1951 and I worked there until 1989. I think I may be the only survivor of that period, even though my lungs are damaged by a progressive and irreversible asbestosis, with diffuse bilateral pleural thickening and bilateral plaques in the diaphragm.

I am one of a group of 1,200 former Eternit employees who are asbestos victims. We have joined together in the Brazilian Association of People Exposed to Asbestos (ABREA), which, in a great display of courage and dedication, fights both in Brazil and internationally for the banning of asbestos and for compensation for asbestos victims.

Allow me to ask you a question, sir, did you ever see any articles about the victims from the Nazi concentration camps? Those who survived are receiving very substantial monetary compensation with all the rights which can possibly exist. When we former employees worked at Eternit we were kept completely ignorant about the fact that we worked in an asbestos concentration camp.

Being good workers, we helped out to the best of our abilities, with total pride and dedication, in building the asbestos-cement empire of the Schmidheiny family. But what did we get from “Mother Eternit?” What we got was a bomb with a delayed action fuse which had been implanted in our chests.

Perhaps you are unaware, sir, but we victims of Osasco, those of us who are still alive, constitute a sort of job guarantee for those who defend the existing Eternit company against its former employees, humiliating us on a daily basis with ridiculously small offers which they call “compensation,” which are especially insulting to those of us with white hair and failing health.

I sincerely hope that I will receive a reply from you as soon as possible, because it always seemed to me that you and your family were not informed about much of what took place in the factories, and also because you seemed like a very caring and respectful person, which has been confirmed for me by the Época Magazine article written by Alex Mansur, and so I beg of you, in the name of the asbestos victims of Osasco, to help us secure the justice which we have dreamed of for those who gave their lives for you, sir, and for your family and your business.”

João Grabenweger died four years later, on January 16, 2008, without ever having received an answer to his appeal to Schmidheiny, his former co-worker, a letter he had waited for until the last day of his life. Eternit offered him US$27.241 to drop his legal suit for compensation.[51]

When Stephan’s father divided the inheritance on the organization, left it to the control of the Swiss Eternit, but wore managing the group since 1975. By 1985, Eternit – Switzerland was already owned by Stephan Schmidheiny and Stephan Ernest Schmidheiny was at that time the second world’s largest seller of asbestos; its asbestos cement operations in thirty two countries produced annual sales of$ 2 billion.[52]

The Swiss Eternit Group had been under the control of the Schmidheiny family since 1920, although undergoing a number of reorganizations and changes in ownership in recent decades; then, in 2003, the Schmidheiny era of Eternit finally ended with the sale to Swisspor Holding.[53]

Stephan Schmidheiny announced in 1978 that Eternit would cease manufacturing products with asbestos, the company, much to Daddy Max’s irritation, gradually pulled out of asbestos cement production. The strategy used to phase out production with asbestos was twofold: on the one hand products containing asbestos were replaced with asbestos-free products; on the other, “dirty” companies were sold.[54]

An interesting aspect to understand the evolution of Stephan Ernest Schmidheiny it is to analyze the traffic that leads him to get rid of the asbestos industry and mutate into a capitalist militancy, where elements associated with the green economy appears as central points of his new shell.

I clarify that the move out of the business of asbestos was determined by a single conviction: Europe had begun to move towards the banning of asbestos and that would make the industry unsustainable. Only until 1981 Schmidheiny decided to publicly announce that the Swiss Eternit Group ceased the manufacture of products containing asbestos. Much earlier than the ban eventually imposed by the European Union announcement, said Schmidheiny in a kind of autobiography entitled “My Path – My perspective”.[55]

Since 1972 Denmark bans the use of asbestos for insulation. And in 1976 Sweden adopts guidelines recommending a ban on crocidolito.

A few paragraphs back Schmidheiny said that security on the carcinogenic effects on human health was not fully demonstrated scientifically. That is, there were doubts. Our advisors believed that the scientific studies purporting to establish the harmful effects of asbestos were rife with contradictions he said. And in Schmidheiny words, the lack of a clear scientific and technical consensus on asbestos and the inherent unpredictability of its effects rendered impossible any reliable planning and risk evaluation.

However, a review of the literature suggests otherwise. Between 1929 and 1935 independent researchers identified the causes and symptoms of asbestosis. By 1940 the scientific community had established links between asbestos and lung cancer, and in 1959 Dr. J. C. Wagner discovery of the link between asbestos and mesothelioma.[56]

The most powerful weapon used to defend the industry against mesothelioma was handling science from within, to create doubts about the toxicity of this mineral.

The Saranac Laboratory in upstate New York was one of the premier institutes researching occupational disease. Saranac had been founded in the 1880s by Dr. Edward Trudeau to treat tuberculosis, but soon branched out into the study of associated lung diseases. Under the leadership of Dr. Leroy Gardner and later Dr. Arthur Vorwald, it conducted some of the most important research into silicosis and asbestosis, invariably with industry funding.[57]

Metlife along with the asbestos conglomerates was among Saranac’s sponsors during the 1930s it commissioned a number of studies. Although Gardner and his successors never testified in court on behalf of industry, the laboratory’s financial dependence on external funding did influence research outcomes.[58]

In November 1936, Raybestos-Manhattan and Johns- Manville funded experiments into asbestosis at Saranac. Having made that decision, Vandiver Brown (Johns – Manville legal adviser) wrote to the them director Dr. Gardner:

It is our further understanding than the results obtained will be considered the property of those who are advancing the required funds, who will determine whether, to what extent, and in what manner they shall be made public. In the events it deemed desirable that the results be made public, the manuscript of your study will be submitted to us for approval prior to publications.[59]

Under that code favourable results were used to defend existing work conditions. When litigation threatened, those same results became evidence that employers could not have known of the dangers. If the results were unfavourable they were suppressed. From the early 1930s, while the industry leaders such as Johns – Manville and T&N invested in research, they also required company doctors to keep abreast of the latest data and to attend scientific conferences.

At a general meeting of the Asbestos Textile Institute at Thetford in June 1965 Karl Lindell, chairman of Canadian Johns – Manville, noted with some pride: “The knowledge possessed by the industry’s doctors on the biological effects of Chrysotile asbestos was not surpassed elsewhere in the world”, Lindell’s observations were true for more than thirty years. Johns – Manville, Raybestos Manhattan, Eternit, and T&N knew everything about asbestos.[60]

However, the first international conference that began to uncover the potpourri of asbestos was held at the Waldorf Astoria in New York in October 1964, before an audience of 300-400 delegates from the international scientific community concerned or knowledgeable about the asbestos topic. The man who led the research was Dr. Irving J. Selikoff, a Jewish New Yorker of Russian descent who worked at the Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan. The title of the conference was: “Biological effects of asbestos.”[61]

Selikoff addition to his work at Mount Sinai had a clinic property of his own in New Jersey, in the midst of a working-class community. It was there that he began to examine patients who worked in a local Unarco (Union Asbestos & Rubber Company) asbestos plant near his clinic. Since 1961, Selikoff wrote to the company asking for access to medical records so that he could study these workers, but he was rebuffed. In 1961, therefore, Selikoff contacted the locals of the International Association of heat & Frost Insulators & Asbestos Workers (the main insulating or lagging trades union). Initially they were suspicious. However, Selikoff’s tact and commitment to discovering the truth won over the union.[62]

Thanks to its good relations managed at Mount Sinai, Selikoff assembled a team for a scientific study. He recruited Dr. E. Cuyler Hammond, the American Cancer Society director of statistics and epidemiology, who had already published a landmark study confirming the link between smoking (another industry that took years to admit the dangers of smoking to human health) and cancer lung. Janet Kaffenburgh, who worked with Hammond in preparing a list of the men in the study. The pathologist Jacob Churg verified the cause of death.[63]

Yet Selikoff’s dataset involved a relatively small number of men (632) the conclusions were strikingly clear: Asbestos insulation work could be lethal. Selikoff’s first study published in 1964 covered workers who were on the union rolls in 1943. When these men were tracked to 1962, they showed that insulators had an excess death rate of 25 per cent, with a heavier mortality than normal from not only asbestosis, but also lung cancer, mesothelioma, and stomach/colon/rectal cancer.[64]

From this report, the asbestos industry felt threatened and with his independent research, Selikoff’s stripped American asbestos industry, which for decades had shown little interest in studying its workers, even in the major factories, let alone in the buildings trades and shipyards.

Max Schmidheiny, Stephan Schmidheiny father, branded to Selikoff as “a crank who did research to make money” inter alia the Selikoff’s investigations trembled a theory that was the glory of Eternit, I mean, that asbestos fibres was safely encased in cement, and in this way, a chemical reaction with the cement removed the fibres toxicity, becoming not dangerous because the fibres are embedded in cement. In fact, asbestos was never locked-in and workers who sawed a/c sheets or worked on brakes and clutches were to develop mesothelioma just like factory workers, discarding that was necessary to inhale tons of asbestos to acquire illnesses.[65]

The following year, “The New England Journal of Medicine” Volume 272, No. 272, listed to asbestos as determiner of mesothelioma. After that, according to the magazine, one could not say that the damage and risk of asbestos was not known, particularly the industry, who grouped in SAIAC cartel, monitored and tried to control much of the information that were produced from the field of medicine in this matter.

In this topic kings are industry and the Canadian government, who always maintained a special interest in keeping alive the flame of this business using lying information to divert public attention. In a recent speech made by Pat Martin, a Member of the Canadian Parliament, who has pleural plaques from working with asbestos as a young man, told the conference: “I love my country but I hang my head in shame when I say [that] Canada … exported human misery around the world.” Calling the Canadian asbestos industry “evil and corrupt,” he said that government support for asbestos producers had been “corporate welfare for corporate serial killers.” One of the outputs of the conference resolutions has been to send a letter to Quebec Premier Pauline Marois, congratulating her by the “courageous stand taken by her government to withdraw financial aid promised to the Jeffrey asbestos mine.”[66]

It is clearly conclusive to admit that this industry based its success on lies and deception. I do not think there are still workers in the world who dare to give their workforce for wages and efforts which will them to win a lung cancer or mesothelioma if they know it in advance, and if the industry were released from the beginning this posed risks to human health, other economic prospects had been.

That is why I find it puzzling to completely admit without a trace of distrust, Schmidheiny’s candid assertions in his books, articles, and newspaper articles that depict him as a philanthropist of the latest contemporary, so perfect and well-intentioned as the art sponsoring by him under the euphemism of Daros Latinamerica, and I say euphemism because in a correspondence I had with the director of this collection (Hans Michel Herzog) he denied any ties between this collection and Mr. Schmidheiny, assuring that Ms. Ruth Schmidheiny controlled everything related to the Latin American collection. And indeed, in the documents creating this “noble” purpose Mr. Schmidheiny not appears according to a document that I would reference.

Faced with the question I asked him who the lady was and he answered that they were divorced. They split right at the time when Ruth Schmidheiny and I started with the Daros Latinamerica collection (sic).

Persons appearing in the document I referred in one way or another are related to Stephan Schmidheiny and this document is dated 2001.

I guess given the facts of the trial of Turin, any link will be deny to not hurt so charismatic and ecumenical work done with the proper Latin American art.

Schmidheiny’s family passion for art is a long standing tradition. In his autobiography he says: “I grew up in a family of art lovers. My parents had a large collection of great French and Flemish masters, as well as significant Hodler collection. They were also personally acquainted with many contemporary Swiss artists. And more forward he adds: “while working for the Earth Summit, I had sustained two grievous personal losses: my father and my brother Alexander had died within a few months of each other. Alexander left me his art collection. Attempting to follow in his steps and continue collecting paintings and sculptures from renowned artists such as Giacometti, Johns, Mondrian, Pollock, Rothko, Twombly and Warhol was both a great pleasure and a daunting challenge for me.

I gradually came to the conclusion that the collection required professional management and that clear concepts should be developed to enable me to set the right strategy for new acquisitions, always, of course, within the quality standards that Alexander and his partner had established. And so in 1995 we founded Daros, an organization based in Zurich and specializing in art.

Today, part of the Daros collection is shown to the public in different exhibitions held at the Löwenbräu complex in Zurich, a remodeled old brewery. Because of my close ties to Latin America, my wife and I created the Daros-Latinamerica collection to support artists in the region and afford them the opportunity to achieve recognition in international markets for themselves and for art in their country. Our third collection, Daros contemporary, focuses on collecting and promoting young art in Europe.”[67]

Let me cite just two notes of newspapers that register and certify this relationship between Mr. Schmidheiny and Daros Latinamerica collection.

http://www.welt.de/print-welt/article699868/Wie-man-sich-bettet.html

http://www.monopol-magazin.de/artikel/20102127/Hier-ist-alles-Koerper.html

The news stories are from 2006 and 2010, well after the creation of the Daros Latinamerica collection.

Why insists Hans- Michel Herzog in denying this relationship, if it is recognized itself as such by Schmidheiny as we just read it?

As it is said by a Swiss journalist and expert on economic issues who know this family very well, it may not be a lie, but the statement of Hans – Michel Herzog is far from being the truth.

Guillermo Villamizar

Bogotá, DC, December 2012.

[1] Schmidheiny, Stephan. “My Path, My Perspective” – Autobiography. Published by VIVA Trust, January 2006 (Second Edition), p. 9.

[2] Available online: http://www.ibasecretariat.org/lka-asbestos-in-colombia-2012.php (cited 24/10/2012)

[3] McCulloch, Jock. Tweedale, Geoffrey. Defending the indefensible: the global asbestos industry and its fight for survival. Oxford University Press. 2008, p. 19.

[4] Available online: http://www.mapuche.info/docs/trivero990420.htm (cited 18-11-2012)

[5] Available online: http://www.lignum.cl/noticias/?id=1122 (cited 18-11-2012)

[6] Available online: http://www.ambiente-ecologico.com/ediciones/informesEspeciales/011_InformesEspeciales_InformeSobreForestacionEnChile.pdf (cited 18-11-2012)

[7] Seguel, Alfredo. Radiografía

[8] Available online: http://www.grain.org/es/article/entries/902-biotecnologia-en-el-sector-forestal-de-chile (cited 18-11-2012)

[9] Available online: http://www.globalresearch.ca/manufacturing-dissent-the-anti-globalization-movement-is-funded-by-the-corporate-elites/21110 (cited 18-11-2012)

[10] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. Laurie Kazan – Allen. IBAS. London. 2012, p. 14.

[11] Available online: http://www.forbes.com/profile/stephan-schmidheiny/ (cited 18-11-2012)

[12] Rossi, Giampiero. La lana de la Salamandra. Ediciones GPS. 2008.

[13] McCulloch, Jock. Tweedale, Geoffrey. Defending the indefensible: the global asbestos industry and its fight for survival. Oxford University Press. 2008, pp. 2-3.

[14] Ibíd., p. 3.

[15] Asbestos. The human cost of corporate greed. GUE/NGL. Brussels, p. 8.

[16] R. F. Ruers and N. Schouten. The tragedy of Asbestos (2005), p. 19.

[17] McCulloch, Jock. Tweedale, Geoffrey. Defending the indefensible: the global asbestos industry and its fight for survival. Oxford University Press. 2008, p. 18.

[18] Available online: http://ibasecretariat.org/alpha_ban_list.php (cited 18-11-2012)

[19] Asbestos. The human cost of corporate greed. GUE/NGL. Brussels, p. 9.

[20] R.F. Ruers and N. Schouten. The Tragedy of Asbestos. Pág 13.

[21] Ibíd, p. 13.

[22] Ibíd, p. 13.

[23] bíd, p. 13.

[24] Available online: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/asbestos_documents/en/index.html (cited 18-11-2012)

[25] Available online: http://ibasecretariat.org/lka-global-asbestos-panorama-questions-answers.php (cited 18-11-2012)

[26] See Hans O. Staub, “Von Schmidheiny zu Schmidheiny,” Schweizer Pioniere der Wirtschaft und Technik, Vol. 61 (Meilen 1994), for the rise of the Schmidheiny family. Also see Werner Catrina, Der Eternit-Report, Stephan Schmidheinys schweres Erbe (Zürich 1985).

[27] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. The Schmidheiny family imperium. Adrian Knoepfli. IBAS. London. 2012, Pág. 21.

[28] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. Eternit and the SAIAC cartel. Bob Ruers. IBAS. London. 2012, p. 15.

[29] Ibíd, p. 15.

[30] McCulloch, Jock. Tweedale, Geoffrey. Defending the indefensible: the global asbestos industry and its fight for survival. Oxford University Press. 2008, p. 25.

[31] Available online: http://ibasecretariat.org/lka_sex_secret_asb_lies_nov09.pdf) (cited 18-11-2012)

[32] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. Eternit and the SAIAC cartel. Bob Ruers. IBAS. London. 2012, p 16.

[33] Asbestos. The human cost of corporate greed. GUE/NGL. Brussels, p. 9.

[34] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. A trial with far-reaching implications. Laurent Vogel. IBAS. London. 2012, p 39.

[35] Roselli, María. Amiante & Eternit : Fortunes et forfaitures. Editions d´en bas. Lausanné. 2008, p, 94.

[36] Italian journalist based in Switzerland.

[37] Roselli, María. Amiante & Eternit : Fortunes et forfaitures. Editions d´en bas. Lausanné. 2008, p,

99 – 103.

[38] In South Africa during apartheid, it was established a territorial zoning based on race. Thus blacks were expelled residing in white areas to the homelands, sort of independent states for blacks.

[39] Available online:

http://www.ecoportal.net/Temas_Especiales/Contaminacion/Fortunas_y_delitos._La_mentira_del_amianto (cited 18-11-2012)

[40] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. Eternit in Brazil. Fernanda Giannasi. IBAS. London. 2012, p. 65.

[41] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. Eternit in Brazil. Fernanda Giannasi. IBAS. London. 2012, p. 66.

[42] When confronted about this contradictory statement by the President of Eternit, that Schmidheiny had continued to participate in the asbestos business in Brazil for over a decade after he had claimed that he had left it forever, Peter Schuermann, Schmidheiny’s spokesperson, responded as follows to the editor of Sonntags Blick on December 30, 2004: “It is correct that Stephan Schmidheiny sold the Brazilian shares in Eternit in 1 988, as I had wanted; neither he nor any of his holdings hold or have held any stock in Brazilian interests of that time. Over the decades there were a number of companies that used the name ‘Amindus.’ In the proceedings made available to me there is no evidence that this is the Amindus Holding in Glarus that you are thinking of; there is only mention of an Amindus Holding and an Amindus Holding AG.” Taken from Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. Eternit in Brazil. Fernanda Giannasi. IBAS. London. 2012, p. 66.

[43] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. Eternit in Brazil. Fernanda Giannasi. IBAS. London. 2012, p. 69.

[44] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. Laurie Kazan – Allen. IBAS. London. 2012, p. 57 -59.

[45] The Asbestos War. Guest Editor Laurie Kazan-Allen, p. 1. Available online: http://www.tv3.cat/multimedia/pdf/0/8/1297178029580.pdf (Cited 18/11/2012)

[46] Available online: http://www.forbes.com/forbes/2009/1005/creative-giving-philanthrophy-bill-gates-of-switzerland.html (Cited 18/11/2012)

[47] Available online:

http://www.ecoportal.net/Temas_Especiales/Contaminacion/Fortunas_y_delitos._La_mentira_del_amianto (cited 18-11-2012)

[48] Stephan Schmidheiny: The “Bill Gates of Switzerland” or “The Godfather” of Asbestos? The Saga of an Asbestos Billionaire in His Own Words. Fernanda Giannasi, p. 7.

[49] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. Eternit in Brazil. Fernanda Giannasi. IBAS. London. 2012, p. 70.

[50] Ibíd, p. 70.

[51] Ibíd, p. 70.

[52] Monopolies Commissions, Asbestos and Certain Asbestos products. (London: HMSO, 1973).

[53] Eternit and The Great Asbestos Trial. What Eternit is now. Adrian Knoepfli. IBAS. London. 2012, p. 28.

[54] Ibíd, p. 28

[55] Stephan Schmidheiny. My Path – My perspective. Autobiography. Published by VIVA Trust, January 2006 (Second Edition), p. 10.

[56] McCulloch, Jock. Tweedale, Geoffrey. Defending the indefensible: the global asbestos industry and its fight for survival. Oxford University Press. 2008, p. 50.

[57] Ibíd, p. 52.

[58] Ibíd, p. 52.

[59] Ibíd, p. 53.

[60] Ibíd, p. 53.

[61] Ibíd, p. 85.

[62] Ibíd, p. 85.

[63] Ibíd, p. 86.

[64] Ibíd, p. 87.

[65] Ibíd, p. 111.

[66] Available online: http://www.ibasecretariat.org/lka-storming-the-asbestos-barricades.php (cited 18/11/2012)

[67] Schmidheiny, Stephan. “My Path, My Perspective” – Autobiography. Published by VIVA Trust, January 2006 (Second Edition), pp. 26 – 27.