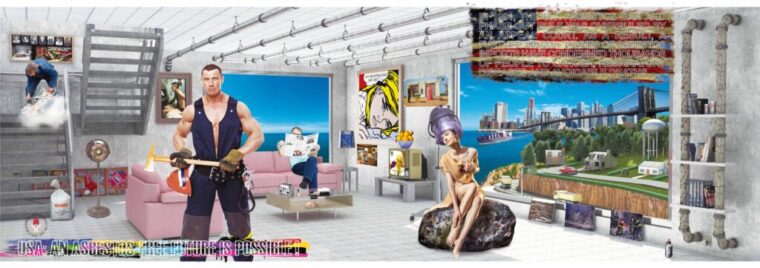

USA: AN ASBESTOS FREE FUTURE IS POSSIBLE!!

This work entitled “USA: An asbestos free future is possible” is part of a project led by artist Guillermo Villamizar, who seeks to visualize the history of asbestos in different countries around the world where the footprint of this dangerous mineral has left a huge impact in terms of occupational, environmental and public health.

The United States was one of the major consumers of asbestos since the beginning of the 20th century. During the 1950s – 1960s and 1970s the average consumption was around 650,000 tons of asbestos, almost all of it imported from Canada by the asbestos giant Johns Manville.

This work is a digital collage assembled from 2D images with the support of 3D software that recreates a half-real, half-imaginary space where all objects – or almost all – contain asbestos to tie together a visual story that tells the story of asbestos in the United States.

The background figure of a man sitting on a sofa upholstered with fabric imported from India in fibers of the lethal material, while reading the New York Times with the headline ASBESTOS: The worst occupational health disaster in America is Ernest Stephan Schmidheiny, the Swiss Eternit magnate who was sentenced in Italy to more than 16 years in prison for the death of more than 3,000 workers in Casale Monferrato, near Turin (Italy), and this opens the puzzle of images that invite the reader to decipher them.

The television set on shows the image of Dr. Irving J. Selikoff, the man of science who, thanks to his research with industry workers in New Jersey, uncovered the rotten pot of asbestos in the United States. Thanks to Selikoff, regulations against this potent carcinogen began to take effect worldwide.

Epidemiology is a thankless task that involves the analysis of hundreds of individuals and their variables, presenting, in some cases, only ambiguous results. The initial conclusions from Selikoff’s database involved a small relative universe of men analyzed (632), but they were powerfully clear. Working with asbestos for insulation was a lethal condition. This first study was published in 1964 and covered workers who had joined the union since 1943. When these men were traced back to 1962, it showed that this type of work caused a death rate of over 25%, with higher-than-normal mortality not only from asbestosis, but from lung cancer, mesothelioma, and cancers of the stomach (peritoneal mesothelioma) and colorectal cancer. This of course was alarming.

By launching this independent research, he managed to unmask, without intending to, the asbestos industry in the U.S., who for decades had shown minimal interest in studying their workers, even in large factories.

That was not the end of it, because Selikoff’s identification of asbestos workers in cohorts became a tool for future exploration. In 1968, Selikoff and his team produced another classic study in epidemiology, and it was to establish the dangers of the synergy between tobacco and asbestos, demonstrating that asbestos workers who smoked were 90 times more likely to develop asbestos-related cancer than those individuals who did not smoke and were not exposed to asbestos.

A decade later, with the help of Herbert Seidman (another American Cancer Society epidemiologist) they were able to provide more information on the tobacco/asbestos and cancer relationship 30 years later and extend the cohorts to 17,800 insulation union workers. It was the largest worldwide study of asbestos workers that Selikoff continued until his death. One aspect that was important in Selikoff’s research was the discovery of the enormous incidences of the dreaded asbestos cancer: mesothelioma. Appropriating an image of the great Pop art artist, Roy Lichtenstein, I transform the question into a Why me? Why mesothelioma? Why me? The inevitable question asked daily by victims of this painful and lethal cancer around the world.

In his opportune moment for him, Stephan Schmidheiny decided to “take his money and run” from Eternit’s impending industrial disaster, and reinvest it in South American forests, building materials companies and electronics companies; in book projects and micro-enterprise support”, universities and “philanthropic” ventures around the world, leaving sick and dying workers in their own factories. He launched himself onto the world stage, magically metamorphosing himself into an environmental thinker and benefactor, and had sanctified that role thanks to institutions of “higher education” such as Yale University, which tastefully dismissed the lethal origin of his multi-million dollar fortune by awarding him an “honorary Doctor of Humane Letters” in 1996. In an interview for Forbes magazine he said, “America is a young and dynamic continent, contrary to Europe, which is becoming old and protectionist.”

In the upper right part, the U.S. flag appears, with a text that gives an account of what happened in 1993, when an attempt was made to ban asbestos in that country and the rule for its elimination ended up being annulled by an appeals court and as a result, more than 300,000 tons of imported asbestos have condemned thousands of people to cancer, respiratory diseases and avoidable deaths. A ban on asbestos is currently being sought in the U.S. Congress.

The woman shown sitting on a huge chrysotile asbestos rock with her hair in the care of a dryer containing asbestos in its heating elements is inspired by Victoria Murdock, a figure with an interesting story.

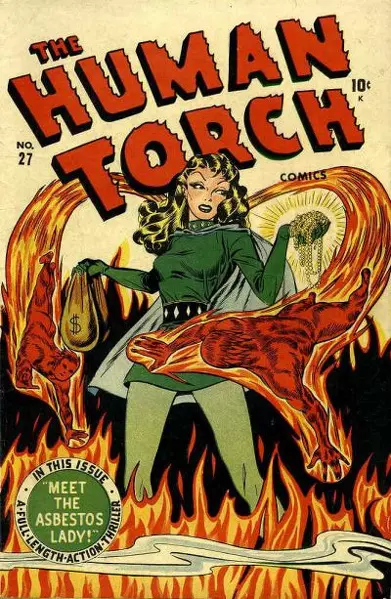

Asbestos Lady was the fictional comic book character originally created by Marvel Comics in the 1940s, but became more prominent when she was reintroduced as Victoria Murdock in the 1960s. Asbestos Lady, a voluptuous and talented scientist, led a life of crime, armed with the powerful properties of asbestos.

In the story, Asbestos Lady uses asbestos to develop her flame-retardant green costume comprising a green miniskirt/dress, purple knee-high boots and a purple cape. Her henchmen were also equipped with asbestos-lined suits and together they engaged in their criminal activities.

Eventually, Asbestos Lady is defeated by her rivals and sent to prison, but this is not the end of her story.

After the dangers posed by asbestos to human health were finally publicly discovered, Marvel, having championed the properties of asbestos, faced a dilemma. Finally, they incorporated it into the story, essentially acknowledging the truth of the dangerous substance and merging fact with fiction. According to the official story, Victoria Murdock, after a lifetime of exposure to asbestos, developed cancer in 1990 and subsequently died of mesothelioma, aged 45.

Not much is known about the origins of the creation of the Asbestos Lady character, although industrial hygienist Anthony Rich posits an interesting version on his website, Asbestorama. Many years before Asbestos Lady was introduced in the Marvel series, asbestos manufacturer Turner & Newall Limited released an advertisement featuring a Greek goddess-like character holding a shield with the word “Asbestos” on it. It is believed that Marvel may have taken this concept and essentially turned this ‘Asbestos Lady’ from good to evil.

Following the visual plot, to the left we find a main figure: a firefighter in a suit with personal protection elements made of guess what? Bingo!

To the left of this man and in the back on the wall is a photograph of Bill Ravanesi.

In the fall of 1980, Bill was informed that his father had malignant mesothelioma. At the time, neither his father nor he had ever heard of this disease. He would soon learn that his father had only months to live, and that this fatal cancer had been caused by his past exposure to asbestos as a shipyard worker in Boston during World War II.

A few years later, Ravanesi came across the book Expendable Americans, written by Paul Brodeur. This book revealed to him the story of how thousands upon thousands of American men and women died each year from a preventable disease caused by exposure to asbestos. His own story of his own tragic encounter with asbestos, along with the information Brodeur’s book provided, led him to make asbestos the subject of his next project. Breath taken: the landscape and biography of asbestos, which he began researching in January 1984, taking it to libraries and bookstores, and then to hundreds of victims and their families. He also visited major industry sites in Canada and the U.S., many of the remaining shipyards, and began talking to professionals in science, medicine and law. He did all this in an effort to use his photographic art to document this preventable human disaster, and suddenly make peace with the fury of his outrage.

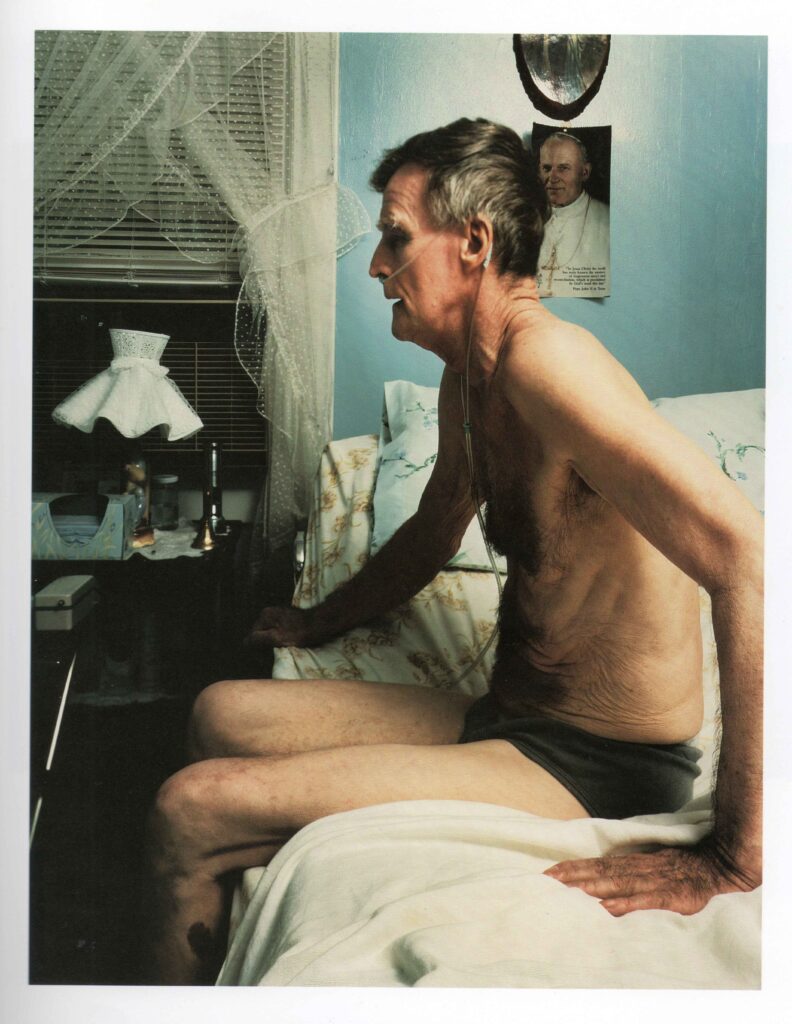

The photograph is of Joseph Darabant who worked in the “E” building at the Johns Manville plant in New Jersey for more than 30 years, cutting asbestos shingles and making asbestos block and pipe covering materials. He recalls that the dust was so thick that most of the time he couldn’t see from one end of the building to the other. When he retired from Johns-Manville in 1974 at the age of 50, JM Medical Center attributed his poor health to chronic bronchitis and a weak heart. He was later diagnosed as having asbestosis. Such is the insidious and progressive nature of this disease that fifteen years later, he had to inhale oxygen through tanks twenty-four hours a day. More than a dozen of his friends and acquaintances at the plant had died from asbestos disease. “If JM had only told us there was something dangerous, we’d all be here today,” he said at the time. “I wish I had some friends. Now, all my friends are in the cemetery.”

The stories surrounding the objects in this digital work are endless, such as the photographs on James Natchwey’s floor during the tragedy of the twin towers that released tons of asbestos into the New York City environment, the asbestos container for heating teapots in the car, the contaminated toys, the Kent cigarette pack with asbestos filters, the floors, ceilings and ducts, or the sculpture that uses a disc for car brakes.

The asbestos industry faced three major crises during the 20th century: the crisis of 1930 when asbestosis was diagnosed in 1924. The second, when asbestos-associated lung cancer appeared in 1940, and the third, and most profound crisis, began with the discoveries of Dr. J. C. Wagner and the link he established between asbestos and mesothelioma in 1959.

One of the important lessons the industry learned during the first crisis was how to use professional associations. They learned how to control information and how to suppress evidence of disease; they learned how to reconfigure a problem about working conditions into a scientific challenge that could be mediated by industry-paid experts. Industry learned how to transform the systematic doubt or methodical doubt that is characteristic of good science into a political weapon. They learned how to corrupt physicians and how to use professional associations to allay public fears. And they learned how to corner – legally and occupationally – those workers who began to know better. All these lessons proved to be of valuable help in the lingering mesothelioma crisis.

An asbestos-free world is possible!

Guillermo Villamizar

Bogotá – 2024