BREATH TAKEN: The landscape and biography of Asbestos”

Preface by Bill Ravanesi for the catalogue “BREATH TAKEN: The landscape and biography of Asbestos”

Some years ago, commenting on his work about mercury poisoning in Minamata, Japan, the photojournalist W. Eugene Smith, stated, “To cause awareness is our only strength.”

In the autumn of 1980, I was informed that my father had malignant mesothelioma. At that time, neither my father nor I had ever heard of this disease. We would soon learn that my father had only months to live, and that this fatal cancer was caused by his past exposure to asbestos as a shipyard worker in Boston during World War II.

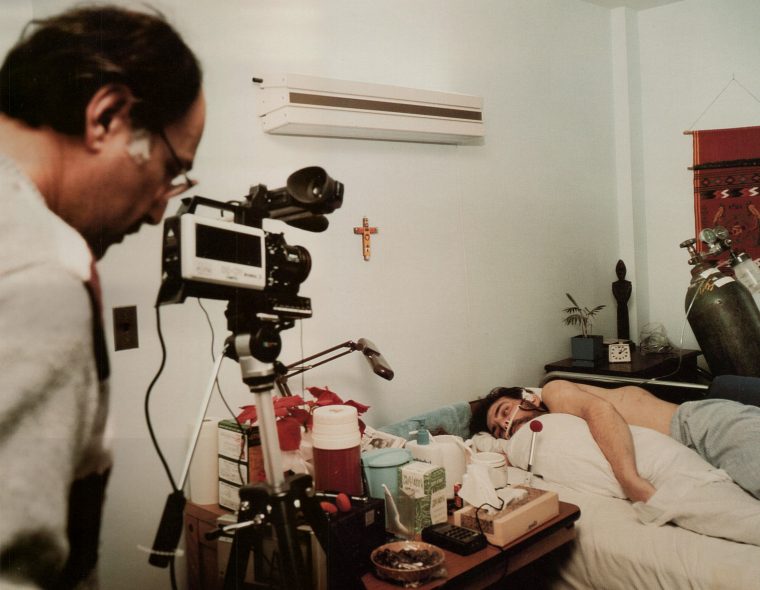

Prior to his illness, my father was 6 feet tall, 220 pounds. In the two months before his death, his weight fell to 160 pounds, he was in constant pain, and was put on intravenous morphine. My family watched, stunned, as he wasted away. Finally, on January 9th, 1981, he succumbed to the cement-like tumors that had invaded the lining of his chest cavity.

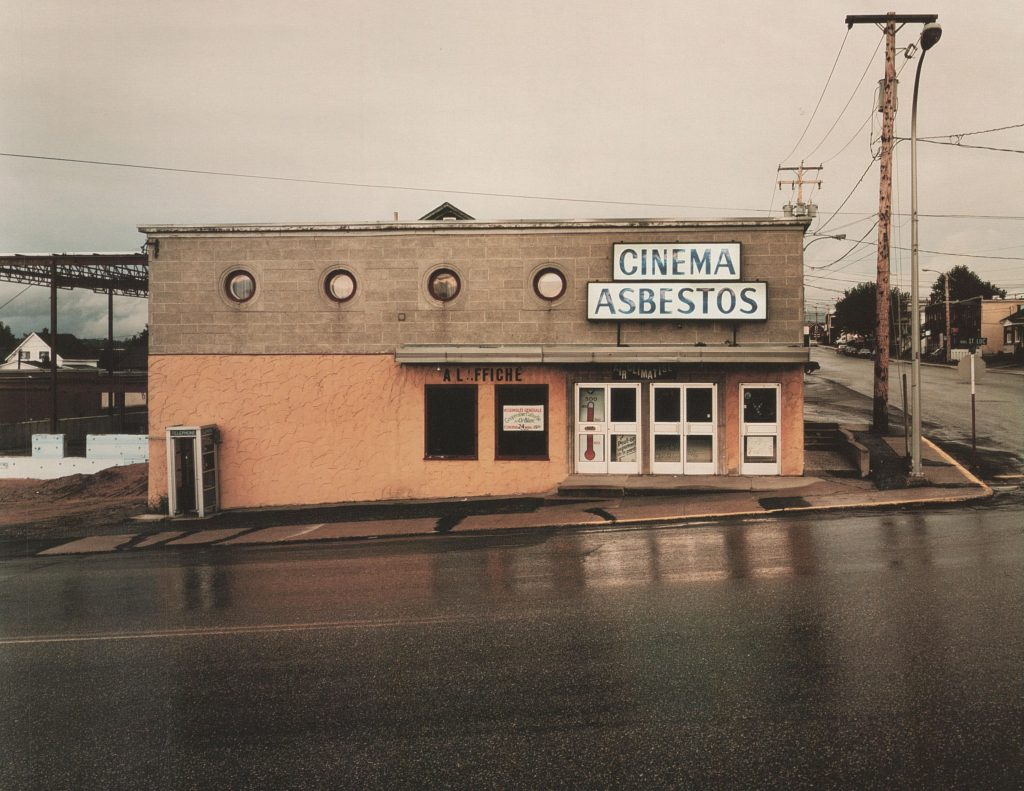

A few years later, I came across Expendable Americans, written by Paul Brodeur. This book revealed to me an incredible story of how thousands and thousands of American men and women die each year of preventable diseases caused by exposure to asbestos. My own agonizing encounter with asbestos, together with my newfound awareness from Brodeur’s book, led me to asbestos as the subject of my next project. Breath Taken: The Landscape and Biography of Asbestos, which began in January 1984, took me first to many research libranes, then to the homes of hundreds of victims and their families. As well, I visited the primary sites of the asbestos industry in the United States and Canada, many of the remaining shipyards, and spoke to professionals in the fields of science, medicine and law. I did all of this in an attempt to use my art to document this avoidable human disaster, and to come to grips with my outrage.

During the early phases of the asbestos project. while I was concentrating on oral history work, it became clear to me that the visual disposition of many of my subjects was very different from my preconceived notion. Of course, images of my father’s suffering were still fresh in my mind’s eye. I had expected that the victims I would meet would have had a similar fate. Although almost all of the victims had scarred lungs, and many were in different stages of various asbestos-caused cancers, many had an outward appearance of health. How does one photograph a victim, who for the most part, looks healthy, but is wasting away from the inside out? In the process of trying to deal with this reality I grew frustrated. Near the end of the first year of the project, I decided to select a small group of victims and to photograph and rephotograph them over a long period of time, creating sequences in which I also included their family snapshots, wedding pictures, and vintage images made earlier in their work careers by company photographers. Some of these sequences stretch over a 40-year period and document the progression of their diseases. In other cases, it became necessary to include their voices so that they could explain that despite their seemingly healthy appearance, they were indeed suffering. This led me to include oral history transcriptions in the exhibition narrative and to produce a video installation piece so that their testimonies could be heard.

Amid the controversies over liability for past exposures and prevention of future instances, the victims of asbestos-caused diseases were and still arc strangely missing from our sight. To the degree that we see them at all, it is usually as objects rather than as subjects—statistics to be recorded, cases to be diagnosed, or plaintiffs to be deposed. Our knowledge of asbestos as a major medical, legal, and social problem has tended ironically to obscure the fact of asbestos as a profound human tragedy that many families have lived and continue to live through. Breath Taken, through its inclusion of both contemporary and vintage images, narrative, industry advertisements, objects, and voice will, I would hope, give the viewer a landscape of awareness of this human tragedy.

Today many people consider the asbestos problem behind us. The EPA has issued a phase-down ban, but what about the 30 million tons of asbestos fibers that remain in place in our society? Asbestos is in buildings like schools, homes, offices and the workplace; in automobiles; in the more than 200,000 miles of transite asbestos drinking water pipe. We, therefore, continue to be faced with important decisions regarding the public’s health and safety. Will our public policies regarding this health menace add to the quarter million deaths already projected for the next 20 to 25 years from asbestos-induced lung cancers alone? Will all this breath taken be in vain?

Bill Ravanesi

Boston. Massachusetts